034 Only Connect

The film commentary of the poet Christopher Mulrooney

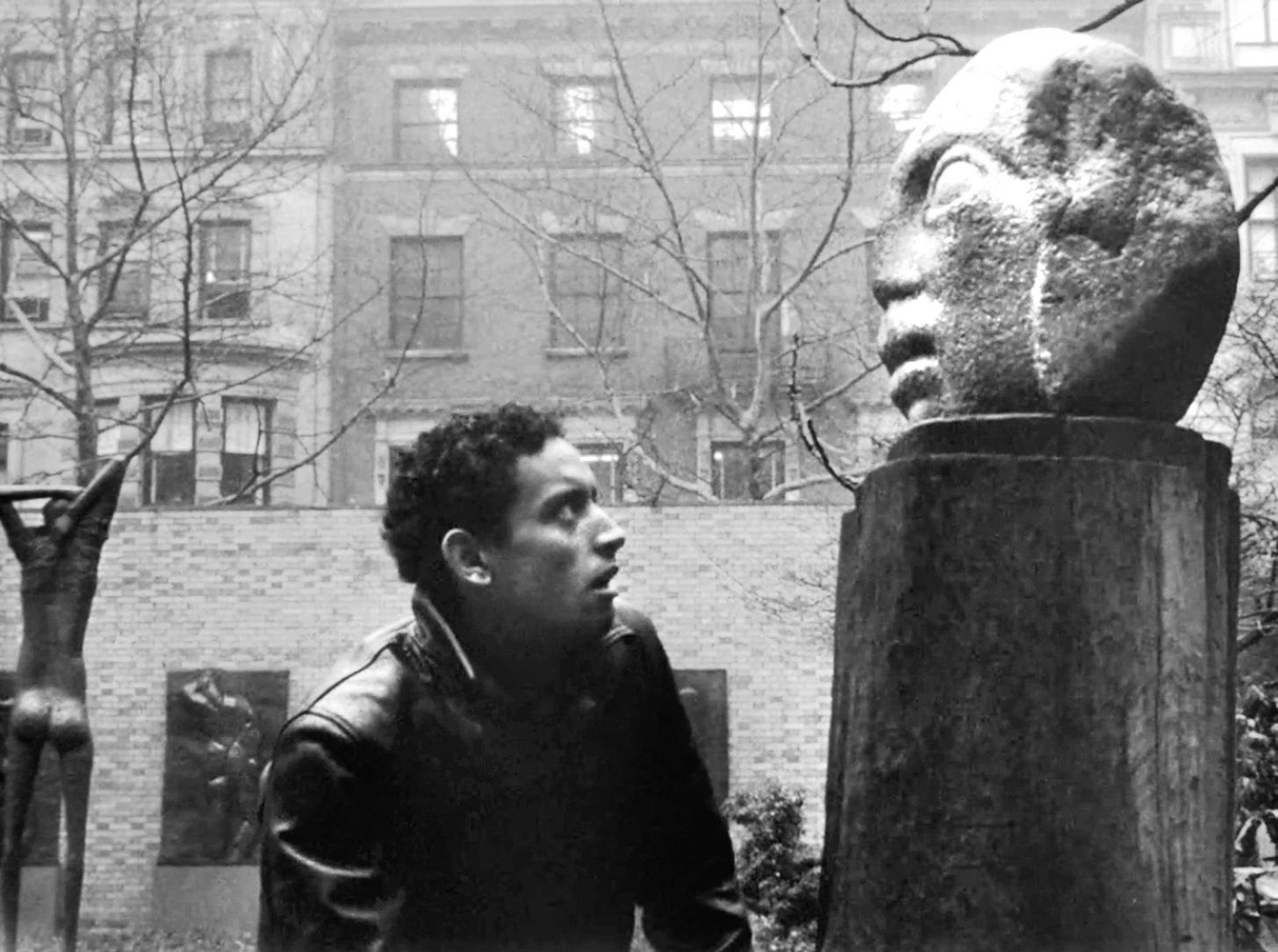

For about two decades I’ve been aware of a corner of the Web that belonged to Christopher Mulrooney, a poet, writer, and photographer.

From time to time I’d peruse his pages and glean a little; maybe recommend them to a friend or acquaintance. On occasion I would try to look up a little more information on Mulrooney, mostly coming across his poems published on other sites. I recently saw that, alas, he died in 2015. I’d actually thought to myself, minutes before discovering that he’d passed on, “I should finally cold email this guy, let him know I think his website is very cool, and see if he writes back.” It’s too bad. From what I can see, he was a brilliant and interesting individual with some dedicated friends. From the sounds of it, he was fascinated by all kinds of art and culture and geography and natural beauty. His omnivorous connoisseurship, if that’s a fair way to describe it, seems inspiring in a modest and energizing way.

Though Mulrooney was a poet, primarily, the work of his that first caught my eye was his page of film criticism; that’s what I’ll be writing about here. By looking at this perhaps minor aspect of his larger literary activities, I hope that I can still do him some justice even without claiming to really “get” him, and I hope it’s clear why I think this is important by the end of the piece.

‘Alliwell That Ends Well, as that section of his site is called, is organized by film director. Each director’s page has commentary on individual titles arranged in chronological order. It’s one of a number of unique individual places on the Internet that one used to see more regularly. The Web 1.0 / personal sites and blogs era of the Internet had a real wealth of individuality that has not survived as well in the transition to Web 2.0. People with the access and inclination who had the chance to share their enthusiasms with the world did so before all the templates of self-presentation and communication scripts were as baked-in as they are now. Web 2.0, and its waves of social media interactions, brought their own positives, and their own affordances of individuality, but who could deny that some good things were nonetheless lost in this changeover? Our conversations and our enthusiasms have become comparatively tamed, as in less free, while verbal expressions have become standardized and group affinities have become polarized. We fit in boxes now, and too many of us readily accept the proposition that because a few new, additional boxes are provided for us to choose from today, this counts as “freedom.” Inscrutability, meanwhile, gave earlier online interactions part of their charm. You weren’t always sure where someone was coming from: individuality was a puzzle pieced together more slowly. Now, online, it’s easy to see a communication from someone—a meme or a comment that one doesn’t understand—and still instantly know that the reason one doesn’t understand it is because it’s for a different audience, a different context. “I’m too old for this reference / I’m not part of this ‘tribe’ / I don’t have the required ‘lived experience.’” But I think the context of interactions before social media—whether online or in real life—often had a “wait and see” component to find out what someone’s whole deal is that is too often lacking today. I’m over-generalizing, of course. But I don’t think I’m saying something false.

So: inscrutability, opacity, patience … I’m not always totally sure what Mulrooney means in his capsules, but by no means does that invalidate them. His work provides an invitation to think differently about whatever movie he’s talking about. This isn’t entirely new, but in our brainsmoothed public culture, criticism is the domain of having a strong opinion and sharing it just so, so that in the (perceived) 4D chess of Discourse, it hits the target (the target = the place on the floor where one drops the mic) and prompts the quasi-intelligentsia to golf clap. But all this is utterly ephemeral, and it makes criticism a merely parasitic and epiphenomenal activity. Criticism should try to understand and connect; it should keep the wheels turning. It’s all ideally connected with the objects of critique. I like to think of it as an unending conversation, if that isn’t too cheesy. Mulrooney’s movie criticism, with its unanticipated and vivid connections, does just this.

So let’s tease out a few different examples—sometimes I’ll quote, sometimes I’ll screenshot:

What a fascinating and concise set of observations. If you spend time on social media, chances are any discussion you’ve seen of Planes, Trains & Automobiles hinges on how it’s the quintessential Thanksgiving movie—or how it’s tidy, saccharine junk. If you want “nuance,” you might point out that the movie is sappy but John Candy crushes it. And so on. Are you bored yet? But here is an original and idiosyncratic approach to the movie in only a few lines! Mulrooney notes “Chaplin is the main ideal” (I’m not sure what he means by this: the everyman sentimentality, perhaps?), but then instantly points to a poem by Robert Frost. How many Discoursers would even imagine such a step to take, let alone to commence with? (Not many.) “A Hundred Collars” narrates the experience of a genteel businessman, held up overnight in a town with one hotel, obliged to share a room with big boor:

A brute. Naked above the waist,

He sat there creased and shining in the light,

Fumbling the buttons in a well-starched shirt.

“I’m moving into a size-larger shirt.

I’ve felt mean lately; mean’s no name for it.

There’s a rough generosity to the roommate, Lafe, and one can see how, yes, there is a kernel of the relationship between Steve Martin and John Candy in that movie.

And then, what a line: “The precision and weight of the players fills the screen”—in order for this not to be a pointless truism, one must understand that precision and weight are not the only attributes of a performer that can, or do, fill the screen—and the precise qualities are, I think, those of Candy’s character’s (inadvertent) saintliness—a mimeographed holy fool for 1987 Middle America?—as well as his “stark insensibility.” (That last phrase comes from Samuel Johnson!) Well, OK, then there are priggishness and want; Steve Martin’s character is the prig, but only slowly does the movie show us what both he and Candy respectively want (i.e., what’s lacking and what’s desired in ways that are not immediately manifest). The experience and the idea of this movie are a little more alive to me now, a little better understood.

Mulrooney’s reflections often conclude with some excerpts or summaries of reviews and critical reputation of the film he’s discussing: antennae picking up on the reception, to which his own words serve, sometimes, as recalibrations. (He didn’t seem to like Sarah Polley’s Away from Her at all, and decided it “turned every critic into Jerry Springer for a day.”) Again, though, the point isn’t simply one guy’s journal about whether or not he likes a movie. He’s … constellating.

You could call his project “auteurist,” because it’s organized by director, although that feels reductive and imprecise even if roughly accurate. Fairly run-of-the-mill Hollywood films make up a lot of the focus, from the silent era into the 21st century. But there are experimental filmmakers, Italian and Japanese maestros, and independent pioneers, too. He offers comments on the disreputable (Andy Sidaris, Barry Mahon), the mundane (Jon Avnet, Lesley Selander), and the canonical (John Ford, Yasujiro Ozu). Unlike some auteurist projects, however (like Sarris’ classic American Cinema), it’s not immediately clear who his Pantheon directors are, and who fits into the lower tiers. Are there tiers? You just need to spend time reading what he says, and see that sometimes Mulrooney explicitly identifies what he thinks is a “masterpiece,” and other times it’s difficult to parse out whether he even likes or respects a movie. His choices aren’t always obvious: his enthusiasm for Fashions of 1934 (William Dieterle) stands out, for a random example. The page on Gerd Oswald mentions neither Crime of Passion nor A Kiss Before Dying but does call Fury at Showdown “an astounding paranoid fantasy.” To me this is great! The ranking of films or directors is, itself, kind of beside the point—it’s more fluid than this—he’s putting them in conversation with each other and with poetry and literature and theatre and many other things. His frame of reference is huge even as his points can be sometimes obscure. You could say about him, “Here’s a guy who has hundreds or even thousands of topics he’s more interested in, yet could probably converse enthusiastically and extemporaneously about the movies of, like, Melville Shavelson.” (Yes, it looks like he could have.)

This certainly isn’t a shrine to his enthusiasms alone, however. Take his dismissal of The Fellowship of the Ring: “A nullity unperturbed by any thought of the cinema. … Airy-fairy to a piss-poor fault, a dismal greenish thing, Yoda’s nightmare. Bad Shakespeare, or rather a run-of-the-mill production of something called The Tragedy of Stentor. Endless close-ups of the titular bauble. Digital hokeshit, whose natal tongue isn’t Elvish but Nerdish.”

What does one do with this line on Slap Shot? “It means neither more nor less than Quine’s Hotel, and that, unfortunately, is everything.” I have no idea what this means, and I really like Slap Shot, but then again I haven’t seen Hotel—maybe I should, to see what it could have in common with George Roy Hill’s shaggy hockey comedy. I can click over to see Mulrooney’s comments on Hotel on the Quine page, but they provoke more questions than answers.

The way he describes Joseph Losey’s The Go-Between, and the unpredictable points of comparison, is beautifully provocative. He’s not talking about genre or plot formulas but something more like, perhaps, cinematic chronotopes.

On Oskar Fischinger’s Motion Painting No. 1, he describes the look and feel of the film (nod to Clouzot-Picasso), but based—spiritually, not literally—on an observation from Nabokov.

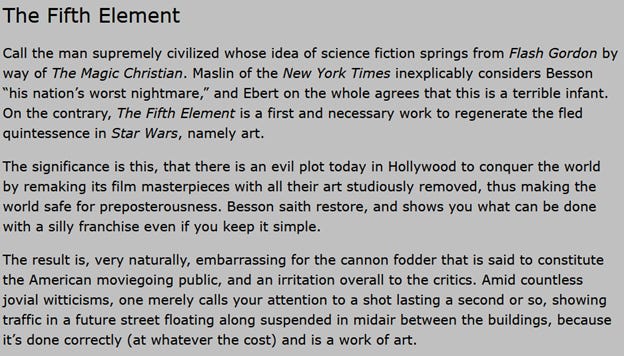

From Fischinger to another kind of kaleidoscopic color-field, The Fifth Element:

This feels too generous to The Fifth Element (a movie I have some fond feelings for), but whether I agree is beside the point. What a counter-intuitive move here: he’s claiming Luc Besson is a filmmaker to reintroduce art into Hollywood!? That sounds absurd to me, on the face of it, but Mulrooney’s reasoning in the final paragraph causes me to pause and think—the amusing inventiveness of a brief shot in the film (I recall exactly which one he’s talking about) is an example of the kind of careful yet disposable surplus that, indeed, once marked Hollywood’s finest periods, when it was most perfectly an amalgamation of routine dream factory with fecund cultural expression.

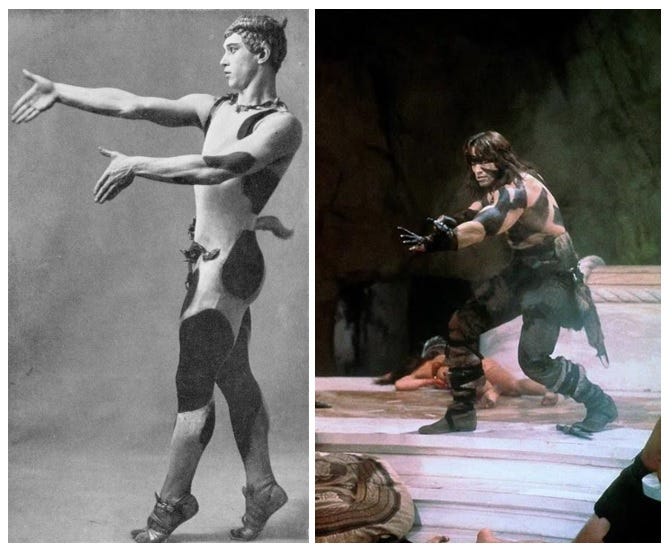

Exploring John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian (1982), Mulrooney casually likens the figure of Schwarzenegger in war paint to Nijinksy’s faun! He doesn’t illustrate this, but I will.

On Shadows, whose improvisational qualities he perhaps overestimates in his longer comments: “Cassavetes’ improvisation on a theme by T.S. Eliot, something of a joke on Bergman’s comical philosophical dilemma over the intermittence of cinema (as compared with the stage). The film is under the twin auspices as it were of Frank Capra (It’s a Wonderful Life) and Hans Richter (Dreams That Money Can Buy, by way of Libby Holman).”

A long essay could be dedicated to probing these connections. This isn’t a question of his being correct, or agreeable, but of being generative, connective. I’m also of the mindset that the sensibility that could come up with that original range of references in relation to Shadows is a sensibility endangered by the standardizations of our current online environment. This is a huge generalization, again, but I don’t think it is wrong. Right now, if you scroll through the feeds (or flip through journals), you will see smart people thinking reactively and predictably from the same, relatively shallow pool of scripts. Christopher Mulrooney and his website are just one example of the kind of weird, associative intelligence—of course I mean this in the best way—that could characterize our discourses, instead.