When I write, I am often most generative in a confessional mode. It’s too bad we’re already hypersaturated with confessional myopia. Plus so much of the writing I admire, and aspire toward, is resolutely not confessional. Or it may spring from the personal to successfully move outward. I think that’s what I’ll attempt to do here, and in the essays that will follow. One has to start somewhere.

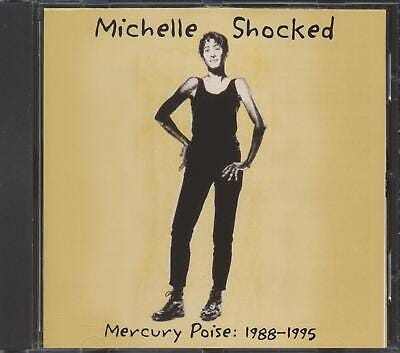

Recently I rummaged through a box in storage and pulled out a Michelle Shocked CD, Mercury Poise 1988-1995. I hadn’t listened to it in a long time and I found myself moved and disarmed anew by some of my favorite tracks. The casual, rootsy, lively music, and the rebellious voice she cultivated, have their effect on me still. This is to be expected. People tend to like forever the music they liked when they were teenagers.

Over a decade ago, Michelle Shocked made what professional wrestling aficionados would call a “heel turn,” and this formerly queer-friendly indie artist made some public statements that alienated many of her fans—including telling her audience that “you are looking at the world’s greatest homophobe.” The sexual fluidity embraced by Shocked in her earlier years seems to have morphed into a born-again fundamentalist position. It should go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway, that in talking about Shocked I certainly don’t share or endorse her more recent statements.

I learned about Michelle Shocked through my late friend and mentor Damien Bona, who gave me this CD as a gift over two decades ago. (Damien’s 70th birthday would have been a few days ago—happy birthday, D!) Her music calls to mind for me a more general and optimistic counterculturalism that feels very much like a home key, and which I associate with the late 20th century (and my adolescence)—in my head and my heart, it constellates with things like Yes magazine, very earnest and verbose web 1.0 communist websites, pre-foodie vegetarian recipes, Jonah—Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000, Amnesty International, liberation theology (or some vague approximation of it), Noam Chomsky, anti-death penalty rallies, volunteering, Steve Earle, and plenty of other people and items. My constellation won’t be exactly the same as anyone else’s. I don’t claim it’s all cohesive and coherent, that it didn’t also emerge from a great deal of naïveté, but this moral-political-aesthetic clustering represented some idea of what it would mean, entering adulthood, to be a person who hoped to be good and to make the world around him good. Much of it still speaks to me in some way. Michelle Shocked was one star in this constellation of things that seemed to make sense. From her song “Holy Spirit”:

Oh a twilight time in New York City

Descending subway stairs

The man whistling out a tune

I paid a dollar for my fare

And we got on the same train

Going uptown down the tracks

And we sang out of tune

To the clackety-clack-clack

And the Spirit Holy Spirit was flowing

Yeah the Spirit Holy Spirit it was a-flowing

I heard that song before I moved to New York at 18, myself, but when I think of numerous times moving through the city and the subway, this song isn’t so far away. I don’t know if I can convince anyone of the effect this kind of passage from a song has on me or that they should feel it too. Maybe I don’t even want to convince anyone. It also doesn’t matter if someone think it’s cringe. I am just trying to point to it. I want to say, “there,” “that.”

Shocked was one of Damien’s favorite singers, and the fact that he was a gay man puts a more intimate sting on her later comments. He was always loyal to the artists he loved, just as he was always loyal to his friends, but some things aren’t so easily compartmentalized. I recall his affection for her song “Come a Long Way”; I too enjoyed the song’s wistful, picaresque quality. The lyrics detail the narrator’s journey after she’s re-repossessed her motorcycle; she’s “gone 500 miles today … and never even left L.A.” The verses travel through MacArthur Park, the Watts Towers, Eagle Rock, and other places, propelled by an insatiable appetite for the city, its sights, its people. The lyrical appreciation of variety feels lived in. Even if it’s all fiction, it’s easy to believe that Michelle Shocked knew what it was like to do and pass through all the things she describes in the song. To the extent that the song, and the singer, have a “vibe,” let’s say, seems epiphenomenal to what’s being narrated.

Contrast this with so much recent cultural production in the algorithmic age, which seems determined to capture first a pre-established vibe, that is, to then work backward from an intended effect that is constitutive of a desired audience. There’s something profoundly projected/projective it. (I think I’ll touch on this more in the next installment.)

When folksy band Caamp (whom I like a lot, actually) sings:

So what do you say, when we're 26

We'll get married just for kicks and

Move out to Alaska way up there

I'll get a job stacking bricks

You stay at home with the kids and I'll

Bring the bacon back home to you, girl

We're making the best of this world

… you don’t necessarily come away thinking these guys have stacked bricks in rural country. I’m not alleging inauthenticity here, by the way. That’s not quite the issue. In fact “26” is explicitly a fantasy. It’s a song about a young guy wooing a romantic partner with an imagined future of a very simple, devoted family life—a life that, demographically, few millennials and zoomers are living. This is not a song about experiences the narrator has had so much as it is about experiences the narrator would like to have had, or would like the audience to accept that he’s had. That, in a nutshell, seems to describe so much of the demonstrative activity in the hustle of musical production, audiovisual creation, and brand management.

In “Anchorage,” meanwhile, Michelle Shocked writes about a letter she gets from an old friend who ended up moving up to Alaska, where (like in the Caamp song) the husband gets a job, and the wife takes care of the kids:

Leroy got a better job so we moved

Kevin lost a tooth, now he's started school

I got a brand new eight month old baby girl

I sound like a housewife

Hey Chel, I think I'm a housewife

The timbre and tone of Shocked’s voice are important; the lyrics alone don’t quite do it justice. The song’s narrator is relaying simultaneously her own response to her friend’s letter, and her friend’s dawning self-realization as she was writing it all down. “I sound like a housewife; oh wow, my friend, I think I actually am a housewife! (What kinds of ambivalent feelings does that draw up!?)” This is not an imagined romantic future but a felt, embodied, embedded, shared experience. Listening to “Anchorage” you can practically hear the members of the friend’s family bustling in the home around her as she writes.

When Michelle Shocked sings about a “skateboard punk-rocker” lifestyle, “foreign telegrams,” bumming around the country, motorcycle rides, abortion and gendered double standards—these are convincing aspects of experience, things that one believes she and people around her lived through. There’s something about human-scaled encounters that still lives in lines like hers, and the work of so many others, yet which seems to have retreated from a lot of its previous cultural habitat in the past generation or so.

What follows will be a series of essays (maybe three or four) that expand piecemeal on this topic and how a quasi-ideology of escalationism overwhelms the scale and value of human encounter. I’ll be probing several discursive areas, including subcultures or networks I’m not really part of, but which I track in at least some capacity because I’m curious to understand my world better. I admit, I do feel a lot of cultural pessimism as a result of what I see. But it’s not simply because I dislike anything new. There are structural reasons for why things are the way they are, and also why many people don’t seem to notice or care, why in fact they accept and crave all of it. That will be one of the threads I hope this subsequent series of essays will tease out and clarify.

I do feel like the current cultural emphasis on authenticity and lived experience has hit a dead end. (For one thing, it sure didn't prevent the rise of fascism or the backlash against "DEI.") I'd like to hear/read/see more art about its creator's fantasy lives, but I hope they're more imaginative than the Caamp song you quote.