059 Notes on Hope

Escalationism II

“Hope, in its strong sense, means trusting faith in the goodness of nature, while expectation, as I will use it here, means reliance on results which are planned and controlled by man.”

— Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society

In my previous installment, I suggested that a certain “extreme” quality establishes signal amidst noise, diminishing the power or efficacy of certain older categories of perception, status, and value. Even when the resultant extreme is ridiculous, or kitsch, it is more likely to command attention in an information-saturated environment. In a related manner, it is easier to impress upon people a picture of the future—the future of the world, or civilization, or an organization—if it is framed in a narrative that reassures us, anxious residents of the present, about yesterday or tomorrow. I’m still working these ideas out and have no clincher to my argument. I’m not quite sure what my argument even is, only that I’m noticing things and trying to tease them out into words and concepts. Nothing that follows is more than half-baked, and I keep evolving my thoughts even as I draft this. But perhaps it will be more productive to process them with anyone who might read this.

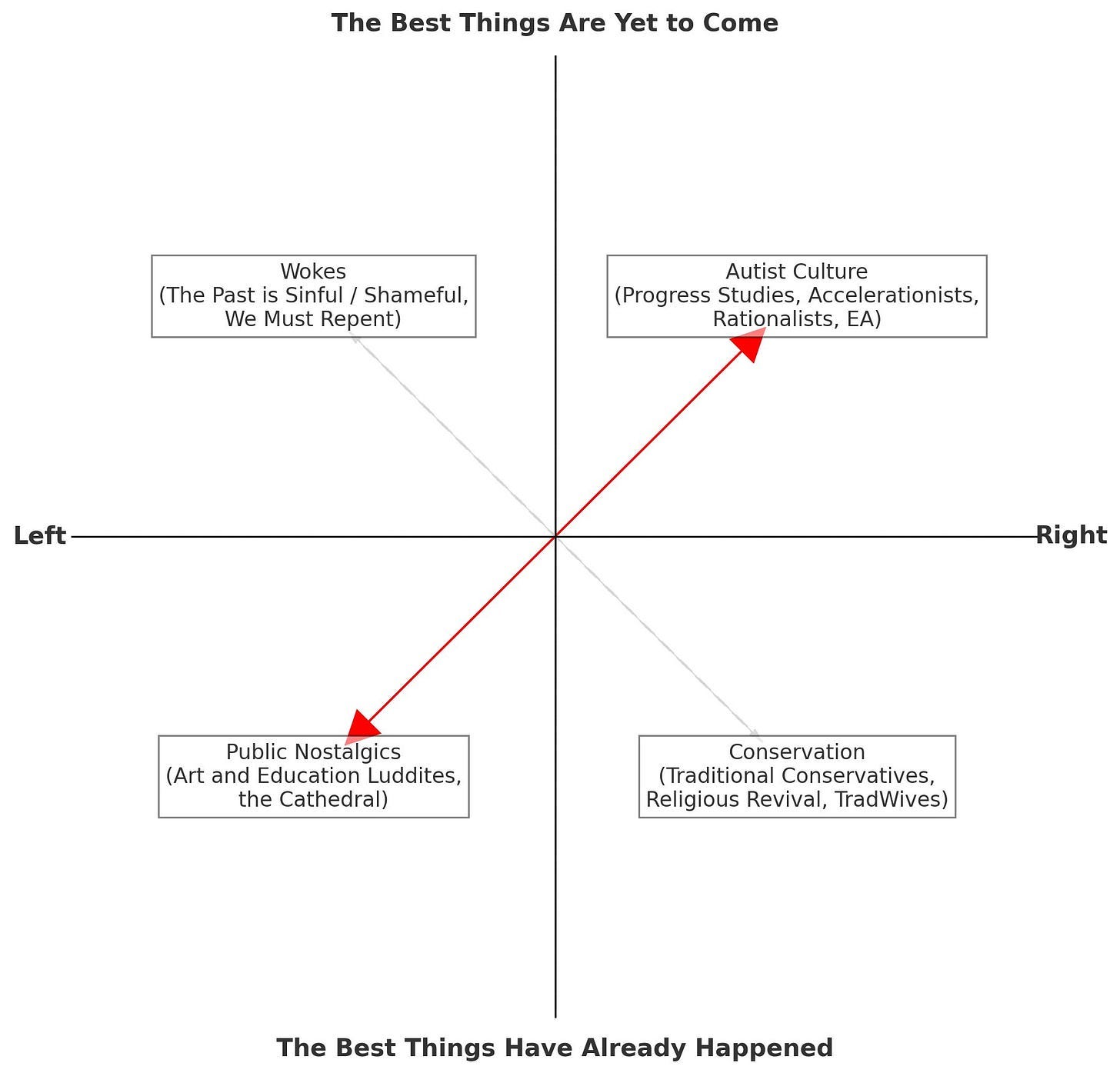

Not long ago, Anna Gát proposed that “the past decade’s cultural standoff between Wokes (past was bad) and Conservatives (past was good) has been replaced” by what she calls an “Autist Culture (future will be good) vs Public Nostalgics (future will be bad) dichotomy.” Gát suggests that we approach this as a question of hope—that this question redefines certain left/right distinctions.

We can see a comparable recasting of the political axis in this piece by Gary Winslett, “Building an Up-Left” politics. Where Gát argues that all of the quadrants in her chart bring value, and that the interplay is crucial, Winslett explicitly crosses the left/right political spectrum with what a writer named James Pethokoukis calls an “up-wing” or “down-wing” orientation. The up-wing is optimistic about the future, and the down-wing is not. In either case, the question of hope—or hopefulness—seems like a central one for the establishment of party or polity. The Up-Left is consonant with an “abundance” agenda, as a recent book, unread by me but covered amply in the mainstream press, would frame it. The Up-Right, I am guessing, maps on to what Adam Becker examines in this book (also unread by me).

The “up-wing,” “hopeful,” or “optimistic” parties in such classification systems cluster according to their aspirations more prominently than their values or principles or shared past practices. Yes, we’re going to save so many more lives with Effective Altruism—or—we’re going to colonize Mars!—or—we’ll see incredible gainz in human knowledge-maxxing with AI—or—we’ll have fully automated luxury communism with full surrogacy now—and so on. There’s a utopian dimension to these not-quite-partisan groupings that is, I believe, absolutely crucial to their continuation and represents (not for the first time in human history) the instrumentalization of hope. These are aspirations tied to calculations.

I don’t say this as a kneejerk dismissal of these ideas en toto. There are writers I follow who belong in or around some of those “up-wing” quadrants who produce very interesting things. But I also will say that a utopianism coming from the ranks of winners, of the affluent and the influential, strikes in me a deep pang of disquiet. The utopianism of oddballs, losers, and the disenfranchised seems more appropriate as a general rule.

Furthermore, I’m worried that the, uh, immanentized eschaton of the techno-utopians—left, right, both—will continue to sever future generations from their human heritage, digitizing some of it, but even then surely denaturing it. This is not because I’m purely a “public nostalgic” (to use Gát’s label) who thinks that our best things our behind us, but because I think that in order for us to have a livable, robust future—culturally and otherwise—we need to preserve the sheer richness of the past. Indeed we should not seek quantified riches at the expense of qualitative enrichment. Doing this requires an openness to what the past can and should offer us, beyond merely a foundation of technical knowledge.

Consider this tweet from Jason Crawford, a proponent of progress studies:

This is a tossed-off comment, not a developed argument, obviously. It is however emblematic of a certain way of approaching the alterity of the past. People who lived 100 or 1000 years ago were embedded in words that may or may not have been entertaining according to the standards of the typical twitter-user but also probably didn't register to them as merely boring. (Tangentially: why assume boredom itself is always bad?) The leisure-and-entertainment environments of 1925 are different than today’s, but if you read literature, memoirs, etc. from the early part of the 20th century, believe it or not you don’t come away from them with the idea that everyone had a Netflix-shaped hole in their lives.

(Or to let Audrey Rouget make the point, when Tom in Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan asserts that Jane Austen’s world is absurd viewed from today’s perspective, “Has it ever occurred to you that today looked at from Jane Austen's perspective would look even worse?”)

Advocates of modernity point out that it’s foolish to romanticize the past too much. We tend to like our speedy travel, consumer goods, abundant entertainment, temperature regulation, low infant mortality rates, modern medicine, and universal suffrage. We shouldn’t lose sight of what a marvel it is that all of these affordances are here for us—many of us—some of us. I actually do agree with a lot of the progress studies crowd on this point about hard-won advances. Yet, it is possible to settle into a dull complacency wherein we cannot fathom other modes of existence than that of a certain type of contemporary affluence, never think to ask what is lost or missing, and cannot even pose the question that maybe some of these achievements have had an ill effect (cf. Illich’s notion of counterproductivity). The imagination becomes blunted and we’re in a poorer position to assess what we might have overlooked.

Returning, then, to the project of capturing sociopolitical realignments via charts and labels, it seems to me that the optimism, or the hopefulness, associated with “up-wing” convictions that “the future will be good” have much more to do with sense of expectation outlined in the Ivan Illich epigraph that opens this installment than with the sense of hope. Hope, understood in this more proper sense, holds the door open for all the variables not accounted for in our rigorous expectations. Anyway, I suspect that between these two concepts is a slipperiness worth examining and understanding better.

More to come …